A sparsely-populated North Atlantic island, Iceland is famous for its hot springs, geysers and active volcanoes. Lava fields cover much of the land and hot water is pumped from under the ground to supply much of the country’s heating.

Iceland became an independent republic in 1944 and went on to become one of the world’s most prosperous economies. However, the collapse of the banking system in 2008 exposed that prosperity as having been built on a dangerously vulnerable economic model.

The affluence enjoyed by Icelanders before 2008 initially rested on the fishing industry, but with the gradual contraction of this sector the Icelandic economy developed into new areas.

By the beginning of the 21st century, Iceland had come to epitomise the global credit boom. Its banks expanded dramatically overseas and foreign money poured into the country, fuelling exceptional growth.

Before the global credit crunch took hold, Icelandic banks had foreign assets worth about 10 times the country’s GDP, with debts to match, and Icelandic businesses also made major investments abroad.

The global financial crisis of 2008 exposed the Icelandic economy’s dependence on the banking sector, leaving it particularly vulnerable to collapse.

In October 2008, the government took over control of all three of the country’s major banks in an effort to stabilise the financial system. Shortly after this, Iceland became the first western country to apply to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for emergency financial aid since 1976.

In the long term, Iceland’s well educated workforce and its extensive and as yet largely untapped natural resources are likely to provide the key to its recovery from the economic crisis, though concerns have been raised over the potential environmental impact of developing the latter.

Environmentalists have protested that a major aluminium smelter project and associated geothermal and hydroelectric schemes were being pushed through at the expense of fragile wildlife habitats.

The country has extended its territorial waters several times since the end of the 1950s to protect its fishermen and their main catch of Atlantic cod from foreign fleets.

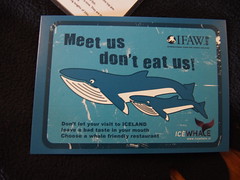

Traditionally a whaling nation, Iceland abandoned the practice in 1989 in line with an international moratorium. It later resumed scientific whaling, intended to investigate the impact of whales on fish stocks, and in 2006 it announced a return to commercial hunts. The move was condemned by environmental groups.

Although it has no armed forces, Iceland is a member of Nato, and US troops were stationed in the country from World War II until 2006. In 1985 Iceland declared itself a nuclear-free zone.

Icelanders were for a long time resistant to the idea of joining the European Union, though the country is a member of the Schengen border-free travel zone and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

Attitudes towards the EU softened, and in July 2009 the country formally applied for EU membership.

EU accession talks began in July 2010, but public support for the project soon waned on account of several factors, including the crisis in the eurozone, a debt dispute with Britain and the Netherlands arising from the 2008 collapse of the Icelandic banking sector, tension over Iceland’s whale fishing industry and popular opposition to the introduction of EU fishing policies.

A conservative and Eurosceptic government elected in 2013 withdrew Iceland’s EU membership application two years later.

More information here: